A diverse gathering of 200 people including students, activists, and journalists convened at Sabarmati Dhaba in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) on Sunday to mark 2,015 days since the arrest of research scholar and Muslim student activist Sharjeel Imam.

The event, organized by of student groups, had impassioned speeches from prominent voices including Afreen Fatima (researcher and activist), Hartosh Singh Bal (executive editor, The Caravan), Advocate Ahmad Ibrahim (legal counsel for Imam), Abdul Wahid Shaikh (author of Innocent Prisoners), Harsh Mander (former IAS officer and social activist), and Sumaira Nawaz (doctoral candidate at McGill University’s Institute of Islamic Studies).

Opening the event, Advocate Ahmad Ibrahim criticized the prolonged legal limbo Imam faces. “There are over 1,100 witnesses in this case. At this rate, it could take a lifetime to conclude,” he stated, adding that the judiciary’s refusal to grant bail despite a lack of concrete evidence underscores the oppressive nature of the UAPA.

Further highlighting procedural delays, Ibrahim said “Even today, in the Delhi riots conspiracy case, charges have not yet been framed. The judicial mind has not been applied so far.”

Following Ibrahim, McGill scholar Sumaira Nawaz pointed to the ideological bias surrounding Imam’s academic work. “If one reads Sharjeel’s research closely, it becomes evident that during episodes of anti-Muslim violence, distinguishing between the Congress and the Hindu Mahasabha becomes nearly impossible,” she remarked.

Nawaz denounced the communal framing of Imam’s scholarship, stating, “Had this research been presented by someone with a non-Muslim name, it likely would have faced none of this hostility.” Questioning the framing of dissent as divisive, she added, “If someone says something or raises a slogan that you don’t agree with, does that make it communal or anti-national? What kind of justice is that?

Veteran journalist and political editor, The Caravan, Hartosh Singh Bal, offered a pointed indictment of the state’s handling of Muslim dissenters. Addressing the gathering, Bal asserted that Sharjeel Imam’s continued incarceration is not rooted in evidence, but in identity.

“Sharjeel Imam is behind bars not because of any proven wrongdoing, but because of who he is,” Bal said. “Had he borne my name, or any Hindu name he would not be facing this ordeal.”

Activist Afreen Fatima, reflecting on an earlier moment of dissent, highlighted Sharjeel Imaam’s contribution in standing against the Babri Masjid verdict. “At the time, no one was willing to protest or even publicly express disagreement with the court’s decision,” she said. According to Fatima, Imam was the only figure who rallied students at JNU to organize a protest against the ruling.

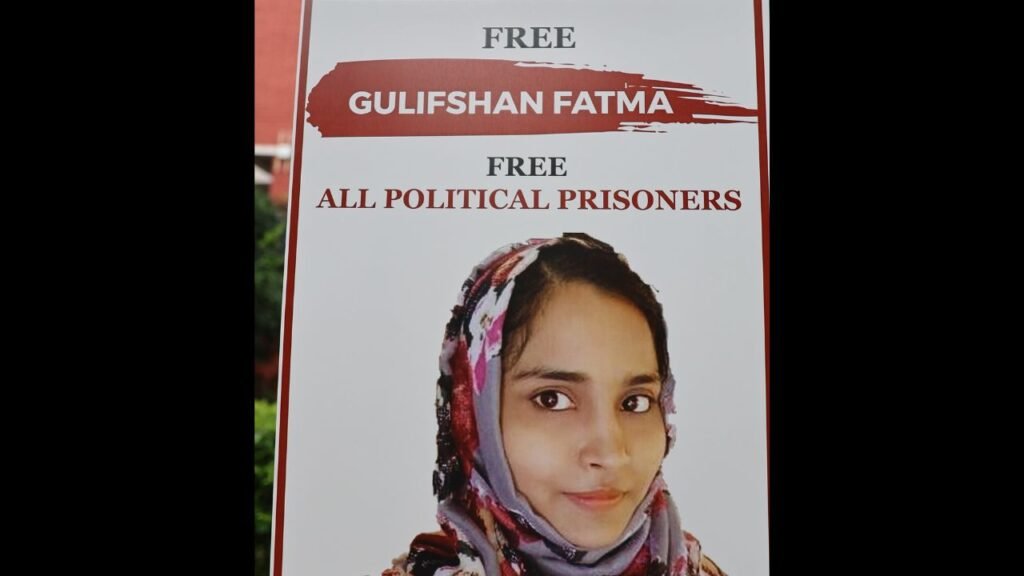

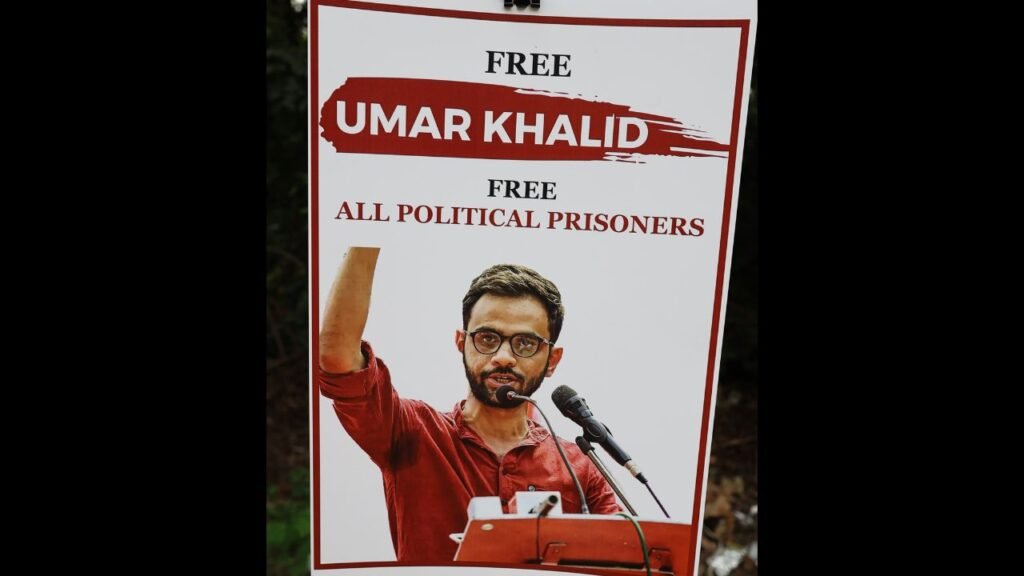

She lamented the continued apathy toward imprisoned student activists, stating, “Even today, despite the sacrifices of Sharjeel Imam, Umar Khalid, and Gulfisha, we remain unwilling to truly stand by them.”

“Even from behind bars, he continues his resistance. But the question remains, are we truly standing by him in any meaningful way?” Fatima questioned.

Walls That Speak, Posters as Acts of Resistance

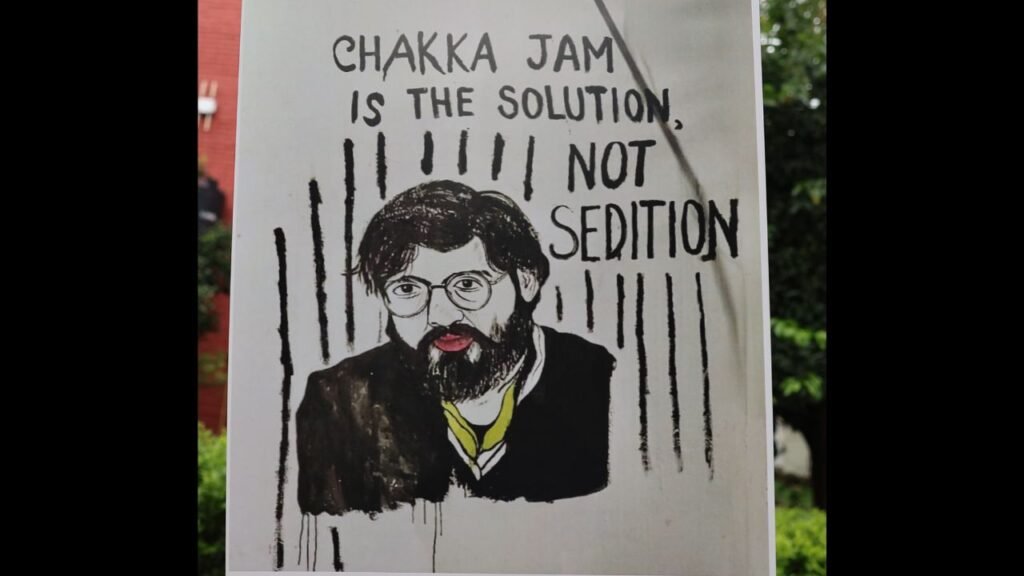

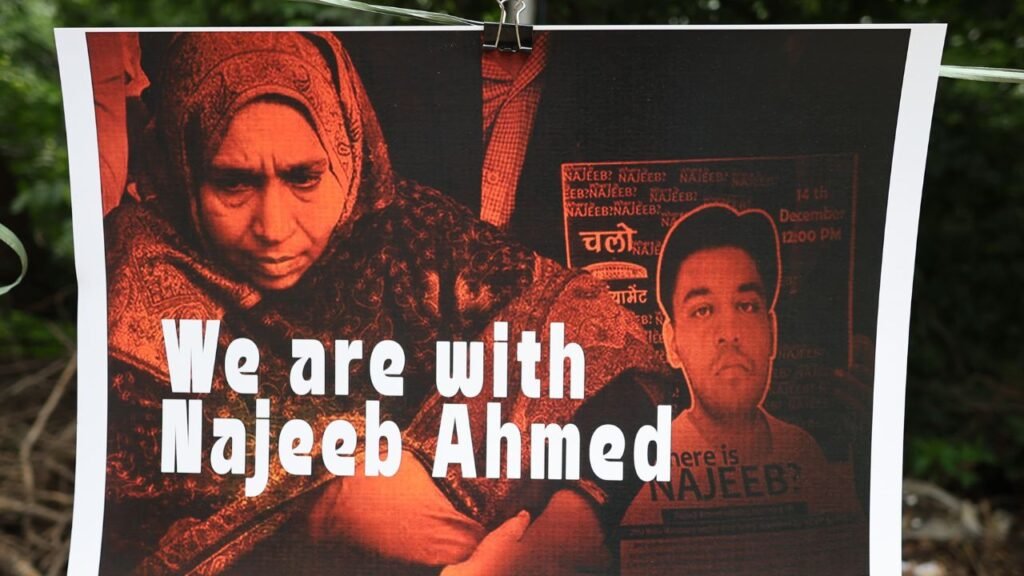

The posters, plastered across walls, pillars, and boards at Sabarmati Dhaba in Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) bore the faces of those who have come to symbolize the cost of speaking truth to power. Sharjeel Imam’s image stood out, calm, defiant, unbroken. Similar posters of other prisoners framed them not as convicts, but as thinkers, students, and activists victims of a system seeking to criminalise resistance.

They demanded the right to remember, to question, and to resist. As students and visitors walked through the campus, the eyes in the posters seemed to meet theirs, urging not just sympathy, but solidarity. In an era of manufactured silence, these posters became a visual protest a loud refusal to forget. For those who stopped to read or reflect, the message was clear: these faces must not fade, and their causes must not be silenced.

The Sharjeel Imaam’s Case

On January 25, 2020, a series of police reports marked the beginning of a mounting legal battle for Sharjeel Imam, a prominent voice during the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) protests. Seven FIRs were filed against him across multiple states. The first five accused him of violating 22 legal provisions, most notably the colonial-era sedition law under Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code. Three of the reports included charges under the stringent Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA).

Subsequent reports deepened the legal quagmire. On March 6, 2020, an additional case charged Imam with conspiracy in connection to the Delhi riots that erupted in February that year, adding 35 more offenses. A December 15, 2019, FIR also linked him to violent incidents at Jamia Millia Islamia University and accused him of serious crimes, including attempted murder (Section 307 IPC) and rioting with deadly weapons.

At the heart of these allegations is a speech Imam delivered during the protests, in which he called for protestors to “cut off Assam from India.” This phrase quickly became the focal point of a nationwide controversy. BJP spokesperson Sambit Patra publicly labeled Imam’s statement as an incitement to “open jihad,” and national media began portraying him as a dangerous radical.

Imam, however, offered a clarification. Just before his arrest on January 28, 2020, Reuters released a statement from him explaining that his intention was to call for a non-violent chakka jam—a blockade of roads and railway lines—as a form of civil disobedience to draw attention to the CAA. He accused the BJP of distorting his words to vilify him.

During legal proceedings, Imam’s counsel, senior advocate Tanveer Ahmad Mir, argued that calls for road blockades do not equate to secessionist intent. He highlighted the dire conditions of Muslim detainees in Assam’s detention camps, suggesting that Imam’s comments stemmed from deep concern over systemic injustices.

Legal experts and activists have also pointed to precedent. In 2008, during the Amarnath land agitation, Hindutva-aligned groups blocked the Jammu-Srinagar highway for days without being branded secessionists. Many argue that Imam’s call for a blockade falls within the same tradition of protest, long recognized in Indian political life.

Despite this context, political rhetoric against Imam escalated rapidly. In the lead-up to the Delhi Assembly elections, Union Home Minister Amit Shah called on voters to “teach Shaheen Bagh a lesson,” a remark seen by many as a direct attack on the protest and its visible figures. Imam was soon labeled a terrorist by authorities and described in court as the alleged “mastermind” of the Shaheen Bagh protests—an assertion that continues to spark heated debate.

As his trial continues, Sharjeel Imam’s case has come to symbolize the fragile boundary between dissent and criminalization in contemporary India, raising urgent questions about free speech, protest rights, and the selective application of the law.

Sharjeel Imam’s arrest in January 2020 followed a wave of criminal complaints filed by police in five Indian states Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, and Manipur amid the nationwide protests against the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). Currently, his cases are being heard in various courts across Delhi.

Among the most serious charges come from Assam, where police invoked multiple provisions of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act (UAPA). These include Section 13(1), which pertains to advocating or inciting unlawful activity; Section 15(1)(a)(iii), which defines a “terrorist act” as one that disrupts essential supplies or services; and Section 18, related to conspiracy.