“But above all he must refrain from seizing the property of others, because a man is quicker to forget the death of his father than the loss of his patrimony”

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince

With the recent enactment of The Waqf Amendment Act 2025, the executive of India has unleashed a new kraken of Hades for Indian Muslims. The alacrity and the manner in which the recommendations of JPC was thrashed in the bin, the parliament was made to function till 2 in the morning, and in 3 days in which it was passed an signed by the Presidents tells a lot about the future of Indian Muslims in times to come. What was more evident was lack of a collective, consolidation blockade to the efforts in delegitimizing the institution of Waqf.

Understanding Waqf

In Islamic jurisprudence waqf refers to the irrevocable dedication of property (whether movable or immovable) for religious, charitable, or public welfare purposes. The property becomes inalienable once it is declared waqf, that means, it can not be sold, transferred, or inherited. The benefit or the income from the property is instead, meant to serve religious or community needs, like, funding education, supporting the poor, or maintaining places of worship.

In the ongoing Sambhal Jama Masjid case, where the legal status and protection of a religious property are being examined, the mosque committee recently filed a plea that is based on this fundamental principle.

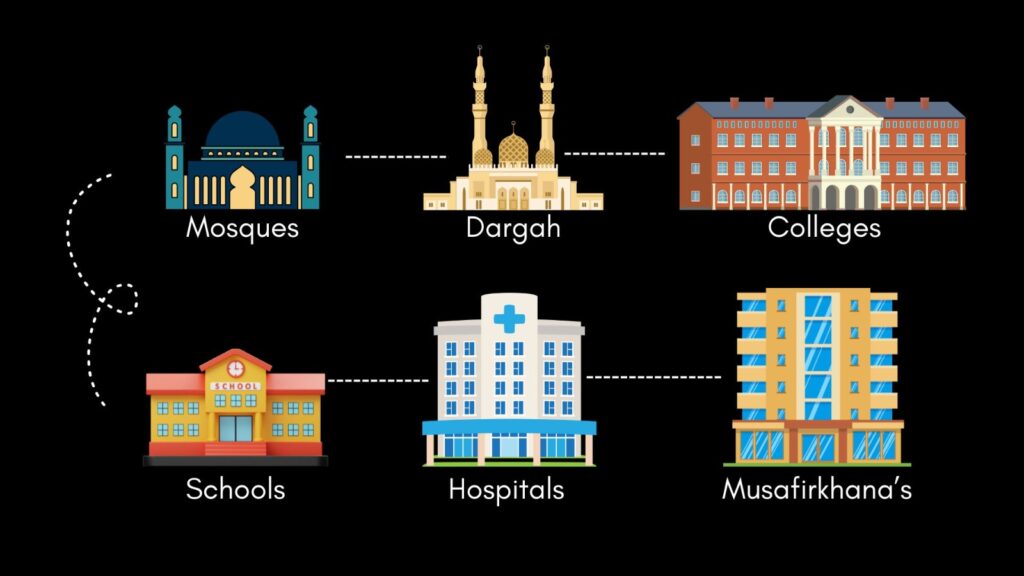

The Arabic word “waqufa,” which means to hold, tie up, or detain, is where the word “waqf” originates. With 3,00,000 properties and 4 lakh acres of land, the Waqf institution in India is 800 years old. The Waqf Institutions deal with the religious, social and economic life of Muslims. They are not only supporting Mosques, Dargah etc. But many of them support Schools, Colleges, Hospitals, and Musafirkhanas which are meant for social welfare.

Tracing of Historical Legal Provisions

The principle that statutory laws, like the Oudh Estates Act, have supreme authority over private or religious customs regarding property management and succession is emphasized by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Thakur Mohd. Ismail v. Thakur Sabir Ali And Others. The Court underlined the importance of adhering to established legal frameworks in estate matters by declaring the wakf-alal-aulad deed invalid for breaking the rule against perpetuities. This ruling not only makes clear the restrictions placed by the Act on perpetual family-oriented property dedications, but it also reaffirms the judiciary’s responsibility to make sure that customs do not conflict with the law.

Absence of Leadership

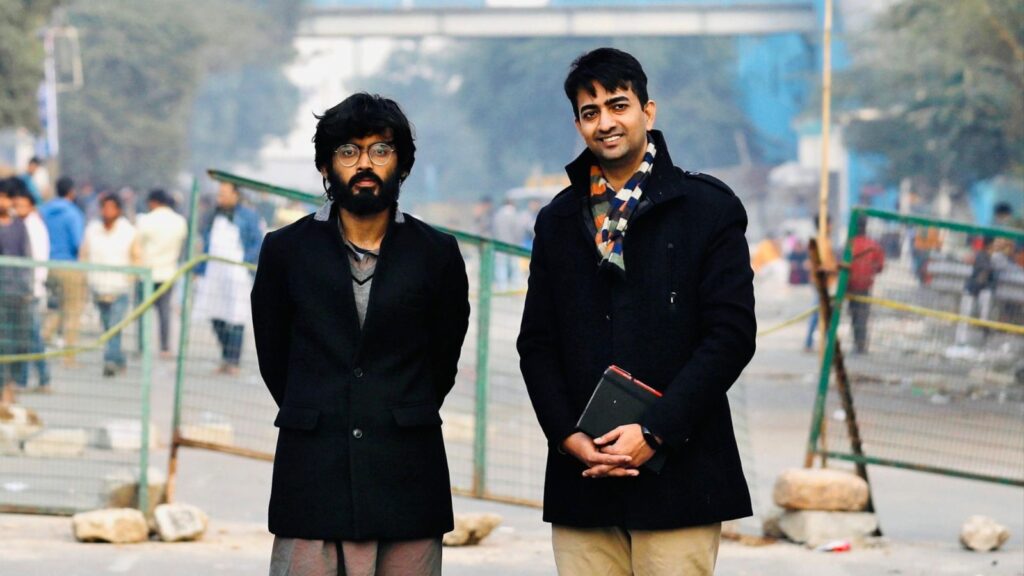

The current situation is a crisis of grassroots leadership. Once marginalized, Muslim leadership in Indian politics has deteriorated to the point where it is now essentially invisible. We need to take a close look at how we got here as a community. Was this lack of leadership always there, or is it a more recent development? Where are the vibrant leaders who surfaced during the Anti-CAA protests’ fervor?

We are all to blame for this failure. At the first hint of trouble, we have learned to desert our leaders. The community fell into silence after the Shaheen Bagh protests when many were detained or questioned. Some even turned away, pretending they didn’t know who they had been standing next to. Such treachery is extremely disheartening.

The few who persisted in the face of criticism are now the targets of constant scrutiny—funny charges regarding their integrity, their visibility, and their motivations. “Why are they trying to get attention?” “They must be stealing money.” “There must be some ulterior motive.” This toxic skepticism stifles genuine leadership.

Let me illustrate with two poignant examples. The first is Wali Rahmani, a young comrade who founded a school for disadvantaged kids with the help of donations from the community and showed remarkable leadership during the Anti-CAA movement. But those who should be celebrating his dedication paint him in a negative light. Unfortunately, those who criticize the lack of leadership also disparage the few leaders who do dare to assume leadership roles.

Why am I articulating this? Because if we truly desire leaders, we must first learn to honor them. The Jamia student who bravely protested against the university’s communal bias deserves our respect. Those who wore black ribbons in defiance and now face legal repercussions deserve our respect. Respect is not optional—it is essential. Ground-level activists inevitably stumble more than armchair critics, but their courage demands acknowledgment. We must recognize this, or resign ourselves to perpetual irrelevance.

Role of AIMPLB

Leadership transcends rhetorical pronouncements—it necessitates audacity, stewardship, and demonstrable efficacy. Archaic institutions like the AIMPLB must either metamorphose or graciously yield to emergent, resolute leadership attuned to this epoch’s exigencies.

The self declared apex body, established in 1973 to safeguard the religious aspirations of Indian Muslims is crippled by a trifecta of inertia: institutional complacency, eroded trust, and a glaring absence of grassroots engagement.

Rasheed Ahmad, ICIM’s Executive Director, contends the Board functions as a bulwark rather than a blade against oppression. He is absolutely right in his opinion. The Board that has become a de facto voice of Indian Muslims has a modicum of work on the ground for making a larger connection. In Uttar Pradesh, over 20 youths were martyred during the 2019 protests—did the AIMPLB console their kin? How often has it stood with victims of lynching or pogroms? Recently When activists faced reprisals for wearing black armbands, where was the Board’s legal solidarity?

Grassroots mobilization demands sustained engagement, not episodic outrage. While the AIMPLB’s sporadic condemnations are acknowledged, the community—bereft of tangible leadership—requires orchestrated dissent, not just censure. As Rasheed Ahmad asserts, true leadership hinges on perilous commitment, not placid decrees. The Board must integrate on-ground stalwarts and spearhead nationwide resistance—calculated, collective, and unyielding.

The Shaheen Bagh

We experienced the same existential crisis five years ago in the icy winter of December 2019. Following the judicial surrender of Babri Masjid and the legislative victories of Triple Talaq and Article 370 abrogation, Parliament’s enactment of the contentious and communal Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) left us feeling betrayed. The intellectuals and Muslim leadership of the era had completely failed to address the youth’s real concerns, and none of them were prepared to take the required risks.

At that point, a group of students from IIT, JNU, Jamia, and AMU stepped up to the plate, using campus protests and the historic Shaheen Bagh sit-in to raise awareness and create a resistance movement. I recall how a well-known Muslim group that is now powerful in the AIMPLB publicly denounced the Chakka Jam (road blockade) in its early days.

The same feelings of betrayal and despair persist five years later. Nothing has changed: madrassas and mosques are being demolished, Muslims are being lynched without consequence, young people are being imprisoned on false pretenses, and hate speech is becoming more accepted. Since graduating, many of the students who spearheaded those demonstrations have gone on with their lives. Sharjeel, Umar Khalid, Meeran, and Gulfisha are among those who continue to be unfairly imprisoned. Others, like me and Safoora, were forced out of our nearly completed academic programs.

The link to the movement becomes less strong once you step outside of an educational setting. The current students on these campuses must now take up the mantle of leadership. It’s time for new leaders to take the lead.

Supreme Court as escape

In recent years, the Supreme Court has become a moral refuge for Muslim intelligentsia and leadership—a convenient sanctuary where they seek solace and preserve their credibility by appealing to its authority, as though it were the infallible arbiter of justice. But let us not delude ourselves. This is the same institution that delivered the communally charged Babri Masjid verdict, the same court that consolidated petitions against the CAA yet denied relief even after five years, the same bench that dragged its feet for over a year before hearing habeas corpus pleas for detainees following Article 370’s abrogation.

Its credibility has long been eroded. Consider the irony: a former Chief Justice, often hailed as the paragon of judicial impartiality, unleashed a divisive interpretation of the Places of Worship Act, 1991, while the current Chief Justice delivers stirring condemnations of bulldozer injustice—even as homes and mosques continue to be razed with impunity. The courtroom, once a hallowed space for impartial adjudication, now stands compromised, its sanctity fractured by partiality and scandal.

This is not to say legal recourse should be abandoned entirely—it remains one of the few remaining fragments of constitutional recourse. But we must not deceive ourselves into viewing it as the ultimate instrument of justice. Not when it dismissed review petitions in the Babri case without due consideration, not when its own judges have been embroiled in corruption, not when some justices openly revolted against their Chief in an unprecedented crisis of integrity. The judiciary may still be a battlefield, but it is no longer the temple of justice we once believed it to be.

The Rough Road Ahead

There is the famous quote” when the parliament becomes a maddog, roads take the lead”We must understand that the key to the entire resistance doesn’t lie with an individual, institution or self proclaimed intelligentsia. It lies solely with the people. A student studying in a school, college or university, a housewife in an obscure city, a shopkeeper or a common individual holds hope. The legislature or the judiciary of the day will deliver justice only if the individual keeps asking their accountability and is ready to take to the streets if they fail to deliver the constitutional promises of equity, equality and egalitarianism.