Long Read —

Imagine a young Muslim man wondering at the weakness of Muslim states in ’50s and ’60s. Yes, The man was Sayyid Qutb! An Egyptian-born Islamic intellectual, Qutb is known for the revolutionary vanguard ‘Muslim Brotherhood’ aside from authoring many literary criticism, novels, poetry, travelogs, and the influential call to action entitled ‘Milestones’ along with a thirty-volume commentary on the Quran.

Qutb’s interpretation of Islam, though rejected by many Muslim scholars, remains spiritual fuel for Islamists around the world.

Sayyid Qutb was a devout Muslim who witnessed the struggles faced by Muslims under the influence of colonialism and the subsequent rise of secular ideologies in the then Egyptian society of mid 20th century.

Understanding the context in which Qutb lived is crucial to comprehending his motivations and the ideas he put forth. His observations of the struggles faced by Muslims, especially in Egypt, compelled him to reflect on the role of Islam in addressing these challenges and inspire a sense of brotherhood, resilience and activism within Muslim communities.

Also Read: New Cairo City and the Rebirth of Egypt’s Civilization

One key element that contributed to Sayyid Qutb’s significant impact and influence was his concept of “Jahiliya.” Traditionally, the term ‘Jahiliya’ is referred to a historical period before the advent of Islam.

However, Qutb expanded this concept to encompass a spiritual condition that can exist at any time and in any society. He argued that Jahiliya represents a state of being where the Shari’a (Islamic law) is not followed, resulting in the rule of humans over humans, which he considered a fundamental violation of God’s sovereignty.

According to Qutub, Muslim states and individuals mimic aspects of Western politics and culture while the West remains politically ascendant and culturally dominant. Since, in Qutb’s time, there wasn’t a single “Muslim” state that ruled according to the Shari’a.

We know that Islamic life – in this sense – stopped a long time ago in all parts of the world and that the “existence” of Islam itself has therefore stopped. And we state this last fact openly, in spite of the shock, alarm, and loss of hope it may cause to many who like to think of themselves as ‘Muslims’!

(Trans. in “Sayyid Qutb’s Doctrine of “Jāhiliyya”.” William E. Shepard. International Journal of Middle East Studizes, Vol. 35, No. 4 (Nov., 2003), pp. 521-545)

For Qutb, Islam was freedom and Islamic society was the civil society, which takes priority to government (Islamic State). In his book “Milestones”, which was originally written in the 1960s, he writes —

“This Din (faith) is a universal declaration of the freedom of man from slavery to other men and his desires, which is also a form of human servitude. Its purpose is to free those people who wish to be freed from enslavement to men so that they may serve Allah alone.” (Milestones)

Qutb’s another significant contribution was that he redefined the Islamic ideal of jihad. The traditional understanding of the Islamic principles of Jihad (= struggle) in its military sense is as a war of defense against non-believers.

Syed Qutb argued that not only was Jihad an offensive war, but that it could also be waged against internal enemies—including the state, if it had lost its legitimacy.

Qutb divided societies into two kinds: Islamic—and ignorant. Ignorant societies were bereft of Islamic principles, values and the Islamic way—and hence illegitimate.

Thus, in a rather laborious manner, he did assert that rulers must govern by the values of those governed in order to be legitimate rulers. When governments, which are formed to reflect and defend the values of society failed to do so, then they lost legitimacy—and could be dissolved or replaced.

The Early Life of Qutub Sayyid

Sayyid Qutb Ibrahim Husayn Shadhili was born in 1906 in the Egyptian village of Musha in the Asyut District, located at the west bank of the Nile and about 235 miles South of Cairo.

At the age of six, Sayyid Qutb’s parents made the decision to enroll him in a modern elementary school (madrasah) instead of a traditional Qur’anic school (Kuttab) where he would have started his education.

Two years after the 1919 revolution began, Qutb moved to Cairo to live with his maternal uncle, Ahmad Husayn ‘Uthman, in order to continue his studies. It was during this period of his development that Qutb was influenced by liberal nationalist forces, which had a significant impact on the intellectual life of the nation in the 1920s.

At this point, Qutb began to develop secular concepts, such as the notion of the separation of religion and literature, which were firmly represented in his writings in the 1930s and 1940s.

In Egypt, the seven-year era before the military uprising in July 1952 was marked by a sense of rage, anguish, and despair at the status quo, which was only made worse by Egypt’s defeat in the 1948 Palestine War. As a result, many Egyptians defected to the two strong opposition parties, the Marxists and the Muslim Brothers, who were willing to overthrow the current order.

Qutb’s dedication to Islam was only strengthened by Qutb’s time in the United States between 1948 and 1950, where he was dispatched by the Ministry of Education to study English and educational curricula.

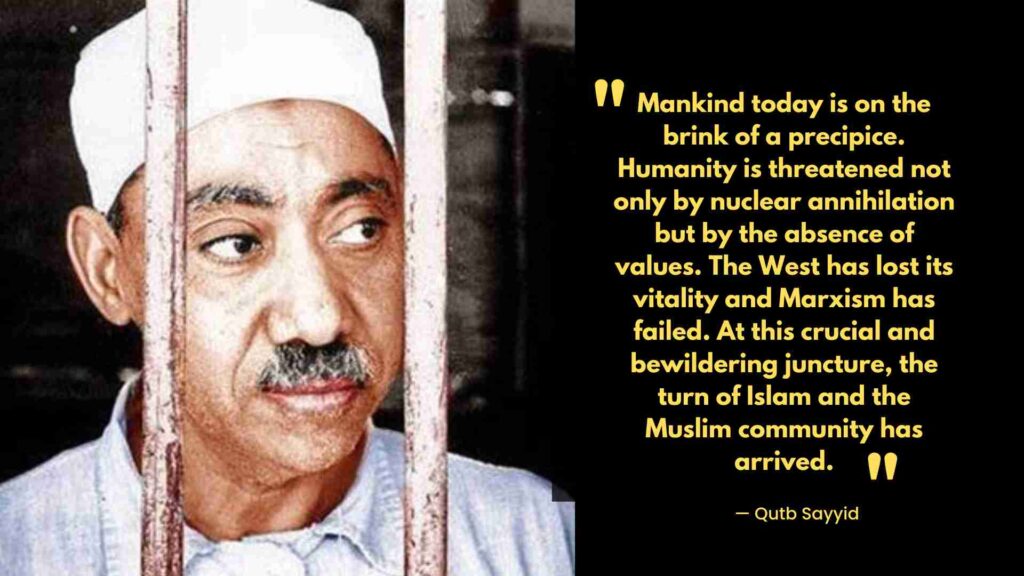

He began to believe that Islam and the Islamic way of life represented the only real hope for humanity in the face of the godless-materialism that characterized both capitalism and communism.

After returning to Egypt, Qutb progressively became attracted to the Society of Muslim Brothers, and in 1952 he became one of the group’s most influential theorists.

Qutub’s theory regarding Muslims and Islam

Qutub saw his ideas as a necessary interpretation and corollary of the basic Muslim creed: “There is no god but God; Muhammad is the Messenger of God.”

His opinions fall within the broad range of Sunni Islamic thought, but particularly the varieties of it that are frequently referred to as “Islamist” (emphasizing the application of Islamic norms in society). He didn’t receive the customary education given to the ‘ulama’ (religious academics), like many well-known writers on religious subjects in recent times, and was largely self-taught in this field.

In examining the various factors that shaped Qutb’s thinking, one of the curious aspects of his biography is that he was radicalized shortly after spending 1948-50 in the United States on an Egyptian Ministry of Education scholarship to study American pedagogical methods. We know that Qutb was scandalized by what he saw at a small church social in Greeley, Colorado (population 20,000), because he wrote about it:

The dance floor was lit with red and yellow and blue lights… Arms embraced hips, lips pressed to lips, and chests pressed to chests….

Upon returning to Egypt, Qutb published his three-part essay, ““The America I Have Seen”: In the Scale of Human Values,” and declared the Americans to be the real primitives.

Qutb explains that the West, armed with science and technology and claiming to be the height of cultural and political progress, has created the most comprehensive Jahaliya ever to cover the face of the earth. It’s so deep that many don’t see it. “The West doesn’t just colonize lands, it colonizes minds”, according to him.

Qutb, therefore, criticizes both the earlier Muslim philosophers and theologians who borrowed from Greek intellectual ideas as well as contemporary modernists who want to “reform” Islam in terms of modern, that is, Western ideas and ideologies.

Qutb employs three stages, namely tasawwur (conceptualization), manhaj (method or program), and nizam (social and political order), to describe Islam and religion in a broader sense. With almost logical necessity, each stage builds on the one before it. Islam cannot live without any of the three.

Qutb frequently asserted that Islam has no “existence,” since he thought that there was no Islamic nizam during his time. It’s important to emphasize that Qutb’s interpretation of Islam is a highly reified ideology rather than merely a catch-all term for a wide range of human beliefs and behaviors.

Imprisonment of Sayyid Qutub

Sayyid Qutb’s resistance to Nasser and the secular policies of the Revolutionary Command Council led to his execution in 1966.

In response to the Nasser government’s strict censorship and press campaign, Qutb resorted to underground activities, such as distributing secret pamphlets, to spread his message. In order to create a unified front against Nasser, it is said that Qutb acted as society’s point of contact with the communists.

He was later accused of collaborating with communists to form a united front against Nasser. Qutb’s involvement in organizing anti-government activities, including incitements delivered from mosque pulpits and the planning of the Muslim Brothers’ disappearance after an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Nasser, further intensified the government’s charges against him.

In 1954, he testified in the trial of al-Hudaybi and admitted to receiving financial assistance for producing pamphlets. In November 1954, Qutb was sentenced to a 15-year term of hard labor for his activism against the government.

Along with other secret pamphlets, Qutb is credited with publishing the covert bulletin al-lkhwan fi-almadraba (The Brothers in the Battle). Other secret pamphlets include Hadhihi al-mu’ahadah lann tammar (This Treaty Will Not Pass) and Li-madha nukafih (Why do we Struggle?)

Activities of Qutub in Prison, 1954–1964

Sayyid Qutb remained imprisoned from November 1954 to May 1964, despite his deteriorating health. He was held in the harsh conditions of Liman Turrah prison. His confinement was harsh and painful. Although he was allowed visits from his family and given writing materials, the government established a commission to suppress his publications.

During his ten-year imprisonment, Qutb worked closely with his fellow inmate Muhammad Yusuf Hawwash, studying the Qur’an together. Hawwash became a reader and critic of Qutb’s writings and was chosen by Qutb as his successor for the underground movement. Tragically, both Qutb and Hawwash were executed by the Nasser regime in 1966.

Martyrdom & After

Qutb’s execution had a different result than was initially anticipated. His martyrdom served to immortalize his name and added him to the illustrious ranks of distinguished Muslim revivalists like Egypt’s Hasan al-Banna and Pakistan’s Abu al-A’la al-Mawdudi.

Legacy of Qutb Sayyid, as manifested in “Ma’alim,” highlights his profound global impact. Till date, his ideas continue to be a subject of discussion and debate among scholars and adherents of Islam.

Follow us on Twitter, Instagram, and Youtube to never miss an update !