The India Hate Lab’s 2025 report documents 1,318 verified in-person hate speech events targeting religious minorities across India — an average of nearly four events a day. While this represents a 13% rise over 2024 and nearly double the figure recorded in 2023, the most significant insight lies beyond the numbers themselves.

Rather than appearing as episodic spikes linked to elections, communal flashpoints, or crises, hate speech is settling into a routine rhythm of political and social life. It is beginning to resemble a routine feature of political mobilisation and public life.

The report finds that 88% of recorded incidents took place in states ruled by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) or its coalition partners. Muslims were targeted in 98% of all events — explicitly in 1,156 cases and alongside Christians in 133. Anti-Christian hate speech was documented in 162 incidents, a steep rise over 2024. The numbers are not just descriptive; they point to a political environment in which public incitement has become easier to organise, safer to perform, and too often met without consistent legal consequence.

A routine pipeline, not isolated outbursts

The report’s category is “in-person” hate speech: political rallies, religious processions, protest marches and cultural gatherings. The report uses the UN’s working description of hate speech and counts only verified in-person events.That detail matters. This is not hatred confined to anonymous corners of the internet. It is delivered in public, through microphones and stages, often in settings that claim cultural or religious legitimacy.

In 2025, the rhetoric did not merely continue; it retained a recognisable structure. Nearly half of all speeches referenced conspiracy theories — “love jihad”, “land jihad”, “population jihad”, “vote jihad”, and newer variations like “thook (spit) jihad”, “education jihad” and “drug jihad”. These narratives do predictable work: they convert social anxieties into claims of organised minority aggression, and then offer majoritarian retaliation as “self-defence”.

That rhetorical structure frequently travels alongside escalation. The report notes 308 speeches with explicit calls for violence and 136 with direct calls to arms. It also records 120 speeches urging social or economic boycotts, and 276 calling for the removal or destruction of places of worship — including mosques, shrines and churches. Dehumanising language appears in 141 speeches, with minorities described as “termites”, “parasites”, “insects”, “pigs”, “mad dogs”, “snakelings”, “green snakes”, and even “bloodthirsty zombies”. When a political culture repeatedly legitimises this vocabulary in public, it is not merely producing hate — it is normalising the idea that hate is permissible.

Where the spikes are — and what triggers them

April saw the year’s highest monthly spike, with 158 hate speech events. India Hate Lab notes that the April spike coincided with Ram Navami processions and rallies that followed the Pahalgam terror attack. In the sixteen-day period between April 22 and May 7, the report documents 98 in-person hate speech events — indicating rapid and geographically dispersed mobilisation.

This pattern is notable: moments of national tension are repeatedly followed by public speech that treats Indian Muslims as a collective suspect population. The report also notes that 69 events targeted Rohingya refugees, and 192 invoked the “Bangladeshi infiltrator” trope — framing Bengali-origin Muslims as foreigners.

These tropes are politically effective because they blur the line between citizenship and suspicion: they translate a security vocabulary into a social licence for harassment and exclusion.

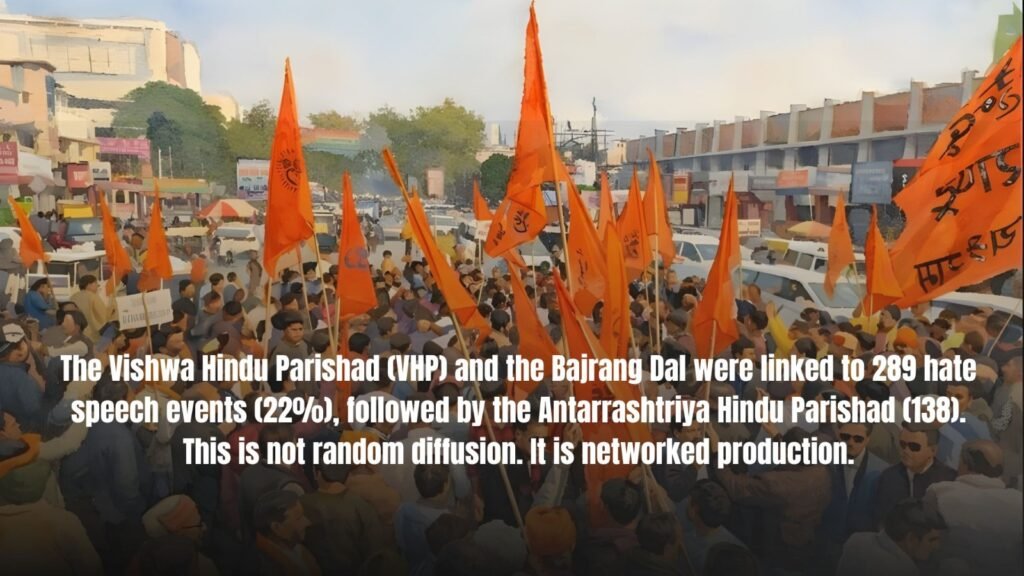

The ecosystem is organised — and increasingly top-down

It is tempting to treat hate speech as the work of fringe actors. The report makes that comfort harder to sustain. It identifies more than 160 organisations and informal groups as organisers or co-organisers. The Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and the Bajrang Dal were linked to 289 hate speech events (22%), followed by the Antarrashtriya Hindu Parishad (138). This is not random diffusion. It is networked production.

The report also names the most prolific hate speech actors. Uttarakhand chief minister Pushkar Singh Dhami tops the list with 71 speeches, followed by Pravin Togadia (46) and BJP leader Ashwini Upadhyay (35). Maharashtra minister Nitesh Rane appears among the prominent actors, and several ruling-party leaders feature among the most frequent speakers.

The point is not only who speaks, but what such speech signals down the chain: when political authority participates in the idiom of demonisation, it reduces the social and legal risks for local organisers to repeat, adapt, and intensify it.

Social media is not the origin — it is the multiplier

The report underlines how closely public hate speech now travels with platform amplification. Videos from 1,278 of the 1,318 events were first shared or live-streamed on social media. Facebook accounted for 942 first uploads, followed by YouTube (246), Instagram (67) and X (23).

This matters because the “in-person” event is no longer the endpoint. A local speech becomes national content within minutes. It can be replayed, clipped, circulated, and rewarded by engagement. Platforms claim rules against hate speech, but the scale of dissemination described in the report points to a persistent gap between policy and enforcement — a gap that functions as digital impunity.

Past the warning stage

In 2023 and 2024, documentation still carried the logic of warning: name the trend, show the numbers, and force public attention. The 2025 data raises a more sobering possibility — not simply that hate speech is rising, but that it is settling into routine. When hate speech becomes predictable in tempo, organised in infrastructure, and safe in consequence, it stops looking like excess. It begins to resemble a method.

The democratic problem is institutional as much as it is moral. A system that allows daily public incitement to flourish without consistent legal cost creates two parallel realities: one in the Constitution, and another in political practice. The India Hate Lab’s report is not asking India whether hate exists. It is recording what happens when hate is allowed to become ordinary — and how quickly the ordinary can become dangerous.

(Sahil Hussain Choudhury is a lawyer and Constitutional Law Researcher based in New Delhi)