While life and death are the two sides of the same coin, one is regulated by the natural phenomena—death, and the other is left to the regulation of the state—life. But from time to time, the debates are occurring on these sides of the coin, the focal point being, should death be a natural phenomenon, should it be an individual choice, or should it be left to the state?

This time the approval of the Terminally ill Adults (End of Life) Bill by British lawmakers has kindled a fierce debate about the morality of assisted dying.

On November 29, the House of Commons voted in favor of the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill. In a “free vote,” MPs were allowed to vote according to their conscience rather than following party lines. The bill was supported by a majority of 330 to 275, with 38 MPs choosing not to vote.

Although assisted dying remains illegal in most countries, over 300 million people as reported by the BBC now live in nations where it is legal. Since 2015, when UK MPs last voted on the issue, countries like Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Spain, and Austria have introduced assisted dying laws, with some even permitting assisted death for individuals who are not terminally ill.

Across the US, assisted dying—sometimes referred to by critics as assisted suicide—is legal in 10 states and Washington DC. Oregon, which was one of the first places in the world to offer assisted dying in 1997, has more than 25 years of experience and has become a model for other US states with similar laws.

In Oregon, assisted dying is available to mentally competent adults with a terminal illness expected to die within six months. The process requires approval from two doctors. Since the law’s introduction, 4,274 people have received a prescription for a lethal dose of medication, with 2,847 (67%) following through.

In the article by the BBC of those who sought help to die last year, two-thirds had cancer, while about 10% had a neurological condition and a similar proportion had heart disease. Among the 367 patients who took the lethal medication in 2023, most (91.6%) cited loss of autonomy as a primary concern. Other reasons included:

- Loss of dignity: 234 patients (63.8%)

- Losing control of bodily functions: 171 patients (46.6%)

- Concern about being a burden on family and friends: 159 patients (43.3%)

- Inadequate pain control: 126 patients (34.3%)

- Financial implications of treatment: 30 patients (8.2%)

In Oregon, as in other US states where assisted dying is permitted, the lethal medication must be self-administered—a provision also proposed for England and Wales. Notably, about one in three individuals prescribed the lethal dose choose not to proceed.

Conditions in Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill by a British Lawmaker would make it legal for the terminally ill patients of age 18 to be given assistance to end their own life. But adhering to the requirements that say:

- They must be resident of England and Wales and be registered with a GP for at least 12 months

- They must have the mental ability to make an informed decision and clearly express their wish, without any form of pressure or coercion.

- Two independent doctors must confirm the person’s eligibility, with a minimum of seven days between their assessments.

- A High Court judge must hear from at least one of the doctors and may also question the dying person or anyone else they deem relevant. There must be an additional 14 days after the judge’s ruling, although this period can be shortened to 48 hours in certain cases.

- They must make two separate declarations, each witnessed and signed either by themselves or a proxy acting on their behalf about their wish to die.

What Supporters and Critics have to Say?

While supporters argue people deserve to die with dignity and that the law would provide dignity and relief to terminally ill patients suffering from unbearable pain, Meanwhile, critics opine that it could even promote disabled people to end their lives.

However, at the heart of the opposition to the bill is a fundamental belief that life, regardless of its circumstances, has intrinsic value. Critics argue that legalizing assisted dying could undermine these values by sending the message that some lives—those of the sick and disabled—are not worth living.

Meanwhile, concerns have also been raised that terminally ill patients might feel pressured into ending their lives, either because they feel like a “burden on their families” or due to the high cost of care. While the bill’s supporters emphasize that the law would allow individuals to make their own choices, many worry that in reality, these choices may be influenced by external factors, including financial or emotional pressures. As some members of Parliament have pointed out, the most vulnerable individuals—those without family support or financial means—could be disproportionately affected by such a law.

Actor and disability-rights activist Liz Carr opposes the law posted on X, “Some of us have very real fears based on our lived experience and based on what has happened in other countries where it’s legal.”

The moral implications of the bill extend beyond the individual to society as a whole. Human rights law, which underpins much of international legal thought, holds that life is inherently valuable and that individuals have the right to live free from coercion. By legalizing assisted dying, critics argue, the state would be endorsing a worldview in which some lives are considered disposable based on an individual’s health or perceived quality of life.

While the bill’s supporters argue that the focus should be on improving end-of-life care, providing palliative care and support that allows people to live their final days with dignity, free from pain, rather than offering death as a legal option.

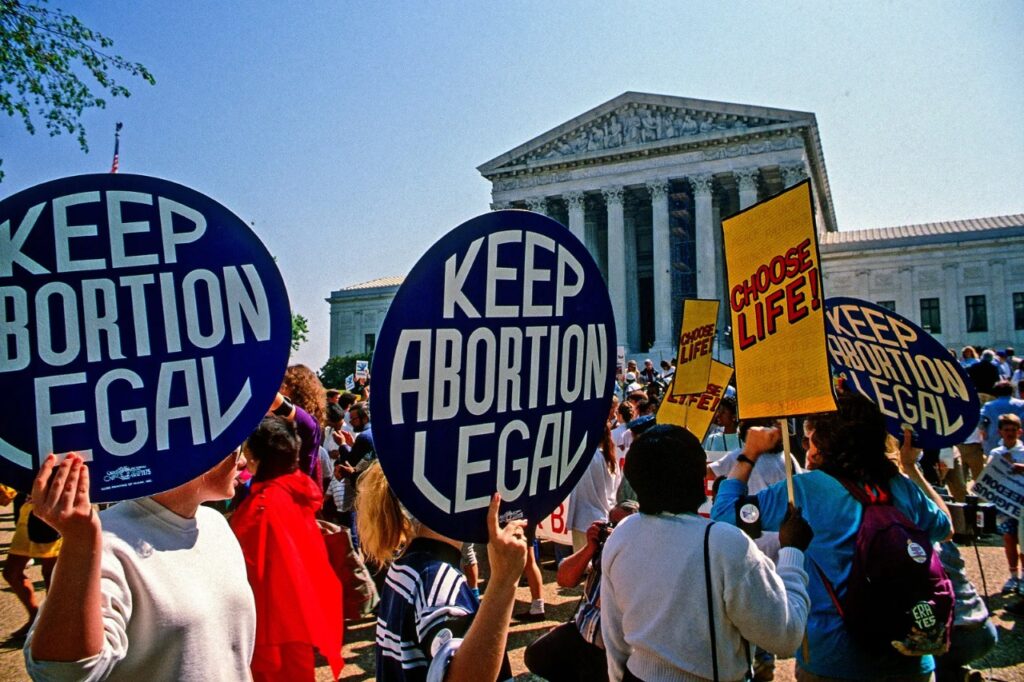

The debate over assisted dying mirrors some of the complex issues surrounding abortion rights, particularly the tension between personal autonomy and the protection of vulnerable groups. The landmark Roe v. The Wade decision in the United States highlighted the legal and moral challenges that arise when individuals’ rights to make personal decisions are weighed against broader societal interests.

Roe v. Wade is a landmark Supreme Court case decided on January 22, 1973, that established a woman’s constitutional right to choose an abortion. The case was filed by Norma McCorvey, who used the pseudonym “Jane Roe,” as she challenged Texas laws that severely restricted abortion access. The state of Texas defended its restrictive law through Henry Wade, the district attorney of Dallas County, which gave the case its name.

On June 24, 2022, the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in its decision on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, ruling that there is no longer a federal constitutional right to abortion. This decision returned the authority to regulate abortion to individual states, allowing them to impose their own restrictions or bans. As a result, many conservative states quickly enacted laws that either severely limited or outright banned abortion access, leading to significant changes in reproductive rights across the country.

From Indian Context

When taken in light of India, the common cause vs Union of India (2018) case is the landmark case. In the case a petition was brought by the common group, a registered society, which argued that the right with dignity formed a part of the right to live with dignity under Article 21 of the constitution.

The case also highlighted that the state should adopt an appropriate measure to permit people with deteriorated health or with terminal illness to execute Advance Medical Directives or a will to live.

This was overturned by a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the case of Gian Kaur vs. The State of Punjab (1996 AIR 946), where the Court ruled that the right to live under Article 21 of the Constitution does not include the right to die. However, in the case of Aruna Ramachandra Shanbaug vs. Union of India and Ors ((2011) 4 SCC 454), the Court allowed passive euthanasia in exceptional circumstances, provided it adhered to the strict guidelines established by the Court.

As the bill moves toward a final vote, lawmakers and the public must carefully consider the moral implications of legalizing assisted dying. While the intention may be to alleviate suffering, the potential risks to vulnerable individuals—particularly the disabled and those without support—cannot be ignored. Instead of embracing assisted dying, society should focus on providing better palliative care and ensuring that those at the end of life are supported and valued, regardless of their circumstances.