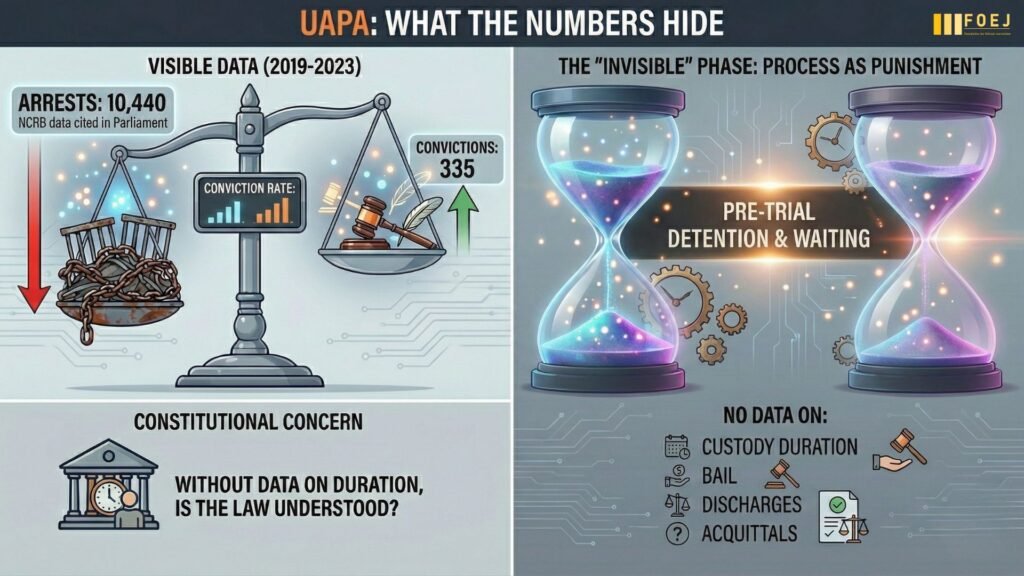

Stand first: Between 2019 and 2023, over 10,000 people were arrested under India’s counter-terror law, according to NCRB data placed before Parliament, while just 335 convictions were recorded – a conviction rate of about 3.2%. The data raises a deeper question — not about the law’s purpose, but about how its process affects liberty before trials conclude.

By Sahil Hussain Choudhury

In criminal law, punishment is supposed to follow conviction. That sequence is not incidental; it is constitutional. Liberty may be temporarily restricted during investigation and trial, but punishment is meant to come only after guilt is established. Yet some laws, in their operation, strain this order. Their most severe consequences can unfold long before a court pronounces a verdict.

India’s counter-terror law, the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, 1967 (UAPA), warrants scrutiny not by examining what happens at the end of a case, but by paying attention to what happens in the years before it ends.

Counting What the Law Shows—and What It Hides

In early December 2025, the government placed data before the Lok Sabha, in response to a parliamentary question, on the use of UAPA between 2019 and 2023. The figures, compiled by the National Crime Records Bureau, disclosed how many people were arrested under the law and how many were convicted during that period.

Over five years, 10,440 people were arrested under UAPA according to NCRB data cited by the Ministry of Home Affairs. During the same period, 335 convictions were recorded nationwide. These numbers were widely reported and quickly absorbed into public debate. Public discussion largely stopped there. Even official government figures confirm a conviction rate as low as ~2–4% under the UAPA.

The same parliamentary reply, however, also contained a quieter disclosure: the NCRB does not maintain state-wise data – or consolidated national data – on how many people charged under UAPA are currently in prison, how long they have been in custody, or how many cases end in bail, discharge, or acquittal. Among states/UTs, Jammu & Kashmir recorded the highest number of UAPA arrests (3,662) between 2019–23, yet only 23 convictions were reported there.

This omission matters. It means that while we know how many people enter the system and how many exit through conviction, we do not know how many remain inside it—or for how long. The law’s most consequential phase, the long stretch between arrest and verdict, remains statistically invisible. Data shows a high pendency in UAPA trials, with most accused remaining incarcerated without conviction for extended periods – a situation aggravated by stringent bail rules.

Why Time Matters More Than Outcomes

UAPA is not an ordinary criminal statute in its procedural design. Bail is difficult at an early stage, investigations may be extended by judicial order, and trials often commence after years have already passed. For many accused persons, the passage of time itself becomes the defining feature of the case. UAPA cases filed in India grew from about 976 in 2014 to over 1,200 per year by 2018 – indicating an increasing trend of use as per NCRB records.

Yet parliamentary data captures only outcomes. It records arrests and convictions, but not duration. It does not tell us whether someone spent six months in custody or six years waiting for their day in court. When debate centres only on final verdicts, the years preceding them fade from view. NCRB data, for instance, records arrests and convictions, but does not track the duration of cases pending trial or the length of time accused persons remain in custody.

In 2022 alone, there were 153 acquittals under UAPA, while only 36 convictions were recorded, showing a troubling balance of outcomes.

From a constitutional perspective, this is not a neutral absence. Article 21 protects personal liberty against deprivation except according to procedure established by law. Critics have noted that between 2016–2020 only ~2% of UAPA arrests led to convictions, with over 97% of detainees still awaiting trial as of the last comprehensive statistics. Delay, when it becomes excessive and unexplained, raises a deeper question: at what point does process itself begin to resemble punishment?

When Courts Take Time Seriously

The Supreme Court has, on occasion, explicitly acknowledged this concern. In a recent case arising from Assam, the Court described it as “appalling” that an accused had remained in custody for over two years without a chargesheet being filed. Even under UAPA, the Court reiterated, investigation is governed by statutory timelines, extendable only by judicial order up to a defined outer limit. Custody beyond that, the Bench observed, could not be regarded as legal “by any stretch of imagination.” Bail was granted.

Such decisions do not weaken counter-terror law. They reaffirm a basic constitutional idea: that time cannot be allowed to operate as an unexamined penalty. Serious offences justify serious investigation; they cannot, by themselves, justify indefinite waiting.

The Human Cost of Waiting

What does this waiting look like in practice?

In July 2020, a Delhi University faculty member was arrested under UAPA in the Bhima Koregaon case. He remained in custody for over five years before being granted regular bail in December 2025. In granting bail, the court noted the prolonged incarceration and the absence of any near prospect of trial completion.

In another widely discussed prosecution arising from the Delhi violence conspiracy case, a former university scholar arrested in September 2020 has spent more than five years in prison as an undertrial. His bail plea remains pending before the Supreme Court. The case remains sub judice.

These examples do not determine guilt or innocence. Courts alone will decide that. They illustrate something narrower but significant: how the experience of UAPA is often shaped less by verdicts than by duration.

What Democratic Accounting Requires

A democracy committed to the rule of law must be able to answer certain basic questions about its most stringent statutes; yet, Parliament itself has acknowledged the absence of this information. How many people are currently imprisoned under special laws? How long have they been there? How many trials remain unresolved? How often is bail granted, and after how much time?

At present, Parliament has partial answers. It knows how many people have been arrested and how many have been convicted. It does not know how many remain in the space between those two points.

This is not a claim of misuse. It is a claim of incomplete visibility. Strong laws require strong safeguards, and safeguards begin with information. Without data on undertrials and custody duration, public debate risks mistaking numerical disclosure for democratic accountability.

Reading the Numbers Differently

The recent UAPA data tells us something, but not everything. It confirms that the law is being invoked at scale. It also shows that relatively few cases have reached final adjudication within the same period. What it does not reveal is the human cost of the years in between.

In constitutional terms, that silence matters. Liberty is not measured only by acquittals or convictions. It is measured in days spent waiting, in years lived under unresolved accusation, and in the strain borne long before a court speaks.

Numbers can inform democratic debate—but only when we ask what they count, and what they leave out. Until time itself becomes visible in our public accounting, the operation of laws like UAPA will remain only partially understood.